Posted 13 января 2023, 10:41

Published 13 января 2023, 10:41

Modified 13 января 2023, 11:10

Updated 13 января 2023, 11:10

Modern Feudalism: Why democracy is impossible in Russia

Russian, but not only, analysts in connection with recent events continue to speculate about what is wrong with Russia? Why has democratization and modernization failed in it once again?

Political scientist Maria Snegovaya, for example, considers it a miracle if the opposite happened, and explains this by the fact that the country's population largely retained peasant attitudes, and also with the experience of serfdom, which was reproduced even during the Soviet era.

Snegovaya refers to the book by the famous American political scientist Edward Banfield "The Moral Basis of a Backward Society", where he explains how such characteristics of peasant communities as 1) a narrow radius of trust, 2) immorality (the categories of good and evil apply only to family members, but not to others members of society) and 3) unwillingness to protect the interests of a group that goes beyond the nuclear family hinders their economic and political development.

The democratization of Russia is very unlikely

Snegovaya believes that although Russians mostly live in cities, Soviet urbanization apparently failed to launch modernization processes similar to urbanization in the West.

There was no class of owners independent of the authorities, the notorious bourgeoisie. In the Russian case, this was overlaid by the experience of the GULAG and the spread of criminal culture throughout the country.

It is precisely these characteristics and the imperial legacy, according to the author, that did not allow a mass national liberation movement like other countries of the communist camp to arise here in the late 1980s. However, chain reactions throughout the communist camp, economic collapse and discontent with the trajectory of the country's development even among the Soviet class of managers launched processes that led to a temporary weakening of the central government in the Russian Federation and the collapse of the USSR. At the same time, since there was no mass national liberation movement in Russia, the elites were not really replaced (no one seriously tried to replace them), the Soviet nomenclature remained at the helm. Even the "liberal" Yeltsin was the quintessence of the Soviet nomenclature.

That is why the population, which temporarily received the lowered freedoms from above, did not fight for them and did not hold on, and it remained a matter of time when the new-old elite would reconsolidate and restart those processes with which it was only familiar in the USSR. It all turned out that way, already in the second half of the 1990s under the weakened Yeltsin, and it became obvious already under Putin.

Therefore, according to Snegovaya, the failure of the democratization of Russia is not a mystery:

"Rather, it is surprising that with such a state of society and elites, at least some kind of modernization and democratization turned out to be possible. Russian society was not civil by the beginning of Perestroika, and it was only by the 2010s that the growth of economic prosperity and the corresponding modernization processes began to create a thin layer of the middle class independent of the authorities (not the one who works for state corporations and law enforcement agencies), who began to demand political and civil liberties. However, its forces (several hundred thousand people) against the elites, merged in tandem with the "deep people", were absolutely unequal. By the beginning of the war, this layer was a maximum of 20% in Moscow, and a much smaller share in other million-plus cities. In addition, since 2012, the Kremlin has been pursuing a consistent policy of destroying this already tiny group in relation to the rest of the country. Most of them will leave or lie low. Therefore, the democratization of Russia is very unlikely even with a change of leadership..."

He called himself a feudal lord – behave in a feudal way

Sergey Pereslegin, a Russian methodologist and futurist, expresses a similar point of view in his interview with Business Online, while expanding the feudal framework in which the Russian population is located:

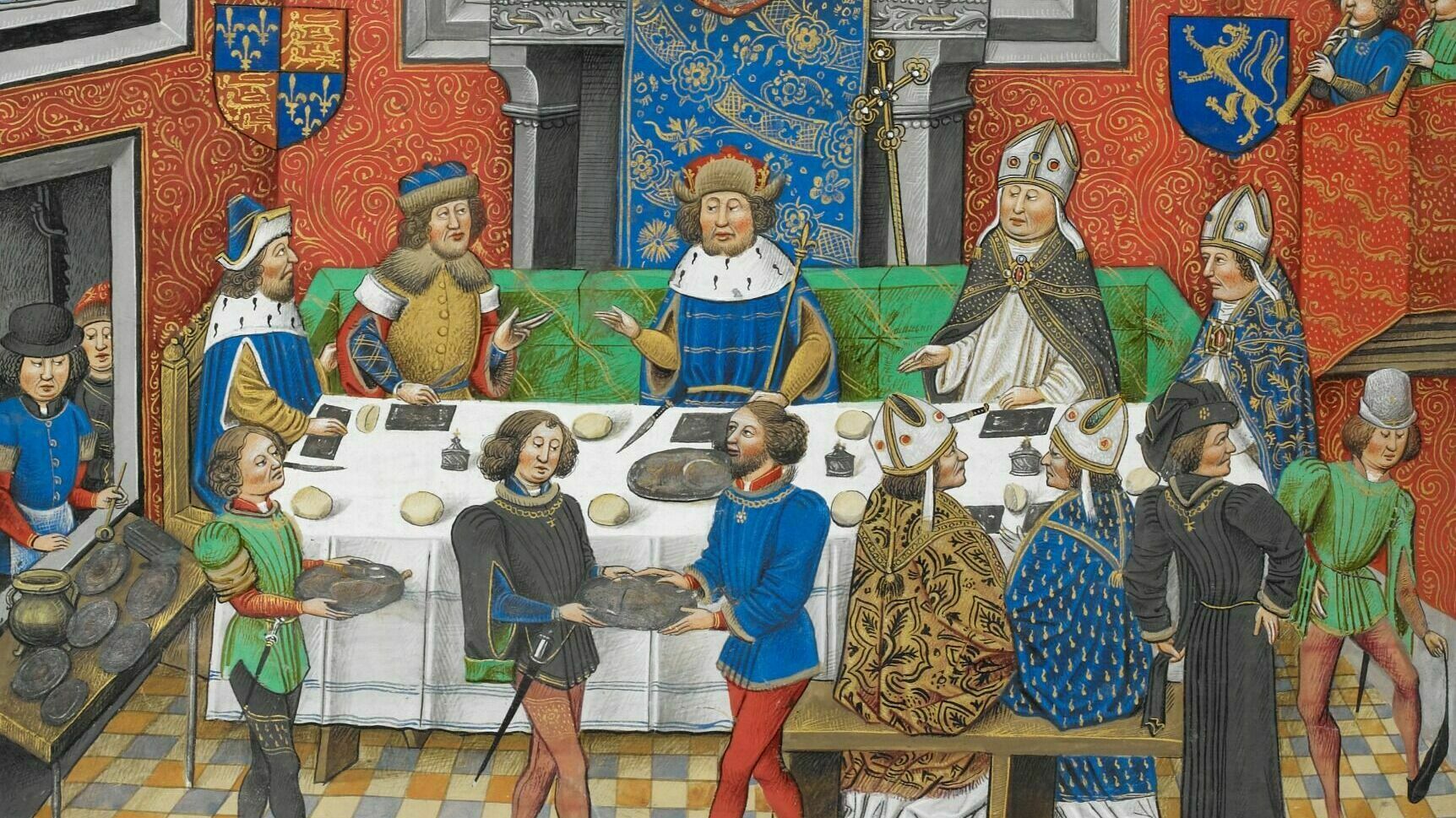

"Russia is in the elite sense a normal feudal state. This, by the way, means that it is pointless to scold the Russian elite for being mired in corruption. This is not corruption at all, this is the usual collection of feudal rent, which it should be. But it must be borne in mind that feudalism is a system that works in two directions. Yes, feudal lords have the right to collect rent from their subjects. But in the event of war, they are obliged, together with their adult sons and in a fully combat-ready form, to appear under the banner of the great leader. This is the demand of feudalism..."

Russia is unlucky not with the people, but with the authorities

Snegovaya's conclusions did not go unnoticed by her readers.

Not all of them agreed with this generalization.

For example, Maya Novikova, a resident of New York, believes that democratic values generally take root very poorly in any country in the world, even in the most civilized:

"On the one hand, from a society that has absorbed some (any) values over the past 30 years, it is possible to squeeze out these absorbed values without a trace in about a year. On the other hand, watching how American society is changing, created, even born, on the principles written in the Constitution of the country, you begin to suspect that human nature is no different in Russia, America, or any other part of the globe..."

And Professor of the University of Pennsylvania Tatiana Mikhailova is sure that it is not the people of Russia who should be blamed for this, but the so-called "elites":

"What is important is not "mentoring", whatever it means, but institutions, rules of the game. Nowhere in Eastern Europe have the people pushed out the elites. Some elites pushed others out. We simply did not have pro-Western elites, or any "non-Soviet" elites at all. "Popular" revolutions are rare. In revolutions, subgroups of elites lead, as in February 1917. Without elites, there is a seizure of power by a gang, as in October 1917. At the same time, the general elections to the Constituent Assembly went well for the people.

Eastern Europe received support in exchange for "renouncing sovereignty" - that is, in exchange for planted Western institutions. That is, double support. Russia has received neither. The institutions were entrusted to the Russian elite to arrange - so they arranged it. The people that you have been so diligently mixing with shit all these months, no one has ever asked about anything, neither about their opinion, nor about their values..."

Journalist and publicist Pavel Pryanikov, who agreed in principle with Snegova's point of view, sees some positive changes in the current situation:

"What was this society like at its foundation, i.e. after the Revolution? The complete expulsion of the entire former management vertical – from the aristocracy to the emerging bourgeoisie and the higher intelligentsia. History knows only one more such example – the Revolution in Haiti at the beginning of the XIX century. For two centuries, this country has not recovered from the changes.

Russia has come a long way in Soviet and especially Russian times. A significant part of the peasants and the village (they made up 90% by the end of the 1920s) became citizens, received basic education.

And after the 90s, these Russians, descendants of the lower classes oppressed for centuries, realized for the first time in history what private property is, the freedom to dispose of their bodies, to move, to receive information. Children's society, in its infancy at the level of "Mowgli", began to civilize and grow up very quickly.

The fact that at least 40% of Russian society has absorbed the basic values of the developed world in just 30 years is a lot. For two centuries after Peter's reforms, these values have absorbed only 5-10% of the population.

All sociological and anthropological studies (Western, like Inglehart, and Russian) show that Russian society is not much different from the societies of its counterparts in Eastern Europe. Especially close to us, if we recall Inglehart's research again, is Slovakia. Poland is also close.

And this is despite the fact that Eastern Europe has fallen under the umbrella of mentors from Western Europe, sharing sovereignty with them. If Russia had been placed in the EU in the early 2000s, I am sure our society would have been even higher than its neighbors in Eastern Europe. Russia was "unlucky" not with the people, but with the authorities. A separate sad story."