Posted 30 марта 2023, 07:26

Published 30 марта 2023, 07:26

Modified 30 марта 2023, 07:56

Updated 30 марта 2023, 07:56

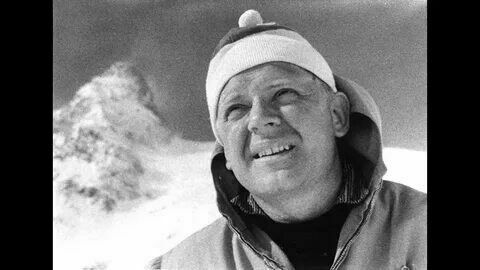

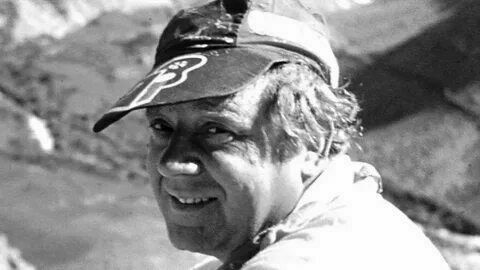

Mountains instead of protest: why the man of the Sixties Yuri Vizbor did not become a dissident

Sergey Mitroshin

One day my aunt, an actress of the Moscow theater, introduced me to a real acting bard, and I just have to remember about him.

The bard seemed to be fixated on mountains, skiing and male friendship. He sometimes wrote short articles about this. The intellectuals of the 70s read them with a smile, or maybe they didn't read them. But in the circle of the same fixated, he was wildly popular. There are no better moments, they say, than to sit by the campfire and sing his songs. Once a Moscow couple even threw out all the furniture from the apartment and pitched a tent in it to continue the sweet illusion. Such romanticism was encouraged by the authorities. Let them go to the mountains rather than to demonstrations. In turn, the "tourists" believed that the whole truth of life is the truth of a tightrope, friendship is when you are pulled out of a crevice, and risk is the risk of a difficult route…

Volodya Vysotsky also sang about it in his program song: "If a friend turns out to be suddenly, pull a guy into the mountains - take a chance! Don't leave him alone..." (1966).

But in a bustling city there was nowhere to pull, you have to live by other standards and shoot rubles. I myself knew one young prosecutor (my brother-in-law in the future, to be honest), not a very healthy and not very brave person in social terms, so the only time he felt good was when he was hanging over the middle-hand abyss of the Soviet Caucasus.

The bard we came to sang about all this and his name was Yuri Vizbor, who seemed to me such a very pleasant and intelligent crook. He sat well-fed, strong and shrewd. In the corner of the normally cluttered room there were huge ski boots and skis. The main thing in the room was a desk with an impressive typewriter. Blocked by strange devices with tangled wires, possibly tape recorders, Yura read a book and pretended to listen attentively.

The aunt who brought me was raving about the new production of the Moscow Art Theater. When she left, Vizbor suddenly looked at me and asked: - And how exactly do you know about me?

The question was not simple, but Visbor was worried about it. The fact is that in the 70s, his surname was practically not found. Apparently, there was some kind of relapse of distrust of bards, even to such "harmless" ones as Vizbor. However, I had his song in my head, which I often heard in my non-constructive age. "Mom, I want to go home," Vizbor sang cheerfully and joyfully on the radio. Memory obligingly fixed the author's surname and put it aside, somehow firmly linking it with the general atmosphere of the 60s. When "July Rain" (1966) went in the "Repeat" with Vizbor in one of the roles, I, of course, also watched it. And Vizbor very convincingly played Martin Borman in the cult Soviet TV series "Seventeen Moments of Spring" (1973). A "Soviet" (by conviction) writer will not be so convincing in the role of the enemy, I also thought to myself.

So approximately I explained everything, with a youthful aggressive habit of asserting myself wherever possible, trying to develop why I did not accept Khutsiev's film.

In the final scene, I said, Khutsiev showed how on Victory Day veterans and their children stand as if they are preparing for the subsequent remaking of the world in accordance with the understanding of higher justice. Unfortunately, by this time, at least to me, it became obvious that the veterans were ours... m-yes... somehow they got tired and that the past tests were quite enough for them. That they prefer to walk on mushrooms and plant potatoes, and their children - to use the benefits due to their fathers for their intended purpose and with the greatest return.

- The film turned out to be unreasonably optimistic, — I said and wanted to add that the author was honestly wrong.

- And you would like him to be justifiably pessimistic, - sneered Vizbor.

That was the end of it, but I didn't understand the meaning of that exchange until years later. In general, the paradox (if I may say so) was that many of the men of Sixties were listed as liberals, but were not dissidents. Lev Krugly, who was given to me as an example in acting courses, said: "I'm not a dissident, because I was afraid and didn't want to go to the camp, so I just left." Zinovy Gerd, whom I also knew, traveled all over the world with the currency theater, volumes of denunciations to the KGB accumulated on him ("his" man from the KGB showed them to him). But Gerd also "pricked" almost on his deathbed: "I've been lying abroad all my life because I was afraid of the security officers who always went abroad with us as employees of the Ministry of Culture." Allegedly, he could not imagine life without "without even our swearing." "I can't live without this vomit. Without those terrible things that happen to us. These are my things. This is happening in my family." Vizbor's father was shot at the Butovo training ground, but he was not a dissident, drawing moral strength not from the uncompromising denial of Soviet power and its derivatives, as Alexander Galich eventually did, but from the legends of male friendship in the last war.

Today, the issue with the political under–formality of the men of Sixties has again escalated when the public suddenly discovered offensive words addressed to Ukraine from the god of Russian poetry - Joseph Brodsky. But he has insulting words against Georgia and Georgians. Isn't the line "Georgian rabble swirling along the tables singing "Tbilisi" offensive? Many began to ask: and if the men of Sixties had lived to this day, who would they have been with? Who would Volodya the Tall be with, who sang about the war as if he had fought himself? Who would Joseph Brodsky be with? Where would Vizbor end up? Could they have evolved into "imperials", as Solzhenitsyn partly became them, or not at all partly the first editor-in-chief of the Perestroika "Nezavisimaya Gazeta" Vitaly Tretyakov? In defense of Brodsky, however, I will note: at the time when he wrote compromising lines, he did not separate Russians, Georgians and Ukrainians. They were all Soviet people for him, that is, "rabble", and he believed that he could call them whatever he wanted.

***

In addition to the strange film "July Rain", which critics dubbed a masterpiece that goes back to the aesthetics of the new wave, the Vizbor of those years was marked by the play "Avtograd XXI", revolutionary in form and, at first glance, retrograde in content, dedicated to the new automobile plant in Togliatti. Vizbor forbade me to criticize myself for her. On stage, the artists of Zakharov's "Lenkom" were proving something pathetically and all this was accompanied by percussion compositions of a certain rock band. Liberal Innovation: A rock band inside a performance. Although, it would seem, what is the revolution here? What does rock have to do with it? In the USSR, even without Vizbor's play and Zakharov's production, factories were built, and factories produced different things. It's like the ideology of the USSR: more factories and more different pieces. Group A should be ahead of group B.

But there was still some kind of revolution in this. The fact is that the Togliatti plant copied FIAT, and the reformers gradually offered to copy everything from the West in general. I read the transcripts of the economic assets of that time, so they proceeded like this. Someone got up and said: look how good vacuum cleaners are in the West, let's make the same one. Or: they have soda machines everywhere, let's put them on, too. It turned out funny with a can of beer. The first cans resembled cartridge cases made of thick metal, since they could only be made with the appropriate equipment. But it is clear that further (than the devil is not joking) you can try to copy both capitalism and the political system. Academician Sakharov framed this into an anti-Soviet theory of political convergence.

If "July Rain" was a masterpiece, it wasn't very... intelligible. It was not clear what was being said and it was not clear about what. Vizbor sang the songs of Okudzhava at random, then his own. The reference to the last war is also visible. But what is it for? Expectation, premonition, or maybe nostalgia for the best years of our lives? Vizbor did not fight – when the war began, he was 7 years old, and my aunt caught the war tangentially in the sanitary echelon, which later caused it to grow into a grand catharsis in her head. The war was even more cathartic for the non-combatants Vizbor and Vysotsky. Well, so it was also natural for the men of Sixties. The war broke Stalinism and softened the regime – which is true. And it is hardly surprising that the men of Sixties managed to close their eyes to the fact that where the Red Army - liberator passed, Chekist dictatorships flourished everywhere. But the situation has really evolved, it seems, successfully. The shoulder master Beria was shot. The World Festival of Youth and Students was held on the ruins of Stalinism in 1957. The Helsinki Conference of 1975 generally opened up incredible prospects for the development of civil society. Who could have known then that the red-browns would not go anywhere, and the KGB in 1991 would only retreat to pre-prepared positions, and that at the end of the road we would face a Catastrophe, which the light has not seen? Neither Vizbor, who died in 1984, nor I, who am still alive, knew this. The tragedy of that generation is (... ah, if it were understood then) that it did not calculate that in the eyes of descendants it would appear (or be forgotten) with the stamp of intellectual prematurity...

The critic Lev Anninsky wrote to the collection of Vizbor's works, emphasizing the timelessness of the Sixties stream: "The generation that absorbed this memory passed its route between the wars: from the last shots of the Patriotic War to the first shots, under which the power began to disintegrate. The generation sang their songs around the campfires — under the crackling of shooting branches. The generation managed to understand where it came from and why it was created before the fire died out".

As for the "July Rain", if you look for its true "masterpiece" in it, then, probably, it will be found in the early idea of the "Beautiful Russia of the Future", when people gather and talk, sing songs to the guitar, Charles Aznavour and Louis Armstrong are heard from the windows, a football match is broadcast on the radio with world teams. Reproductions of paintings demonstrate the universality of this "beautiful Russia", given in dreams. It could all be like this… Or it could have been broken again. Russia is like this: something liberal begins, and then the "greys" come.

When Vizbor "left", I wrote:

For Yu.Visbor, with sadness]

Maybe not everything is as we wanted,

Maybe our shoulder load is not a load,

But still we fought with blizzards,

And we went down a steep descent,

And we crashed into the snowdrifts with skis,

Expelling all the spleen from the pores,

Overgrown with red beards,

Flaunted — the romantics of the mountains.

There was a guitar frenzy, and the scope, and the hotel,

But there were moments when you would have asked:

"Did you do everything the way you wanted before?"

But there's pain on the side, and don't waste too much energy...

The sun beat into my eyes, the hops of the frosty sky,

There are still dates and deadlines behind the cordon,

You don't know where the goal of the crazy run is,

And you don't know where the string will lead us,

And then we're in apartments, and there's nowhere to go,

I myself will reap my bitter sprouting by forty,

It's like you wanted to stay in that childhood,

Where the hell did you get up on the ski run,

Only the table is getting more massive, only the chair is getting deeper,

In the days of the forest — like a confused boy...

We wrote about the same thing — about mountains and friendship

And they carried everything to the same place — in a frivolous magazine...

From the editorial office of "NI":

This publication is a chapter from the author's unpublished book "Atlantis was a country, and the Atlanteans were living people".