Posted 10 февраля 2023, 11:05

Published 10 февраля 2023, 11:05

Modified 10 февраля 2023, 12:55

Updated 10 февраля 2023, 12:55

The Way of Judas and Pavlik Morozov: are informers useful in modern Russia?

Yelena Petrova, Natalia Serova

DENUNCIATION IN THE STATISTICS MIRROR

Denunciation is a delicate matter.

According to sound thinking and expert opinions, the concepts of a snitch and an agent should be strictly separated.

A snitch is a person who denounces a neighbor in order to solve his personal problems. An agent is a citizen who informs the authorities about an upcoming or committed crime, which is the duty of every citizen in any civilized country. However, in practice, it is often almost impossible to clearly separate one from the other.

According to official data, during the year the number of citizens' appeals to the "competent authorities" with information about the "wrong" behavior of certain persons reached more than 130 thousand.

This is 4 times more than in 2020 and twice as much as in 2021.

The wave of struggle against pornography, suicides and LGBT people has passed – there are two times fewer such statements. It was replaced by a campaign against extremism (a 6-fold increase in appeals). There are 124 thousand more statements about illegal activities. Apparently, this is how the official Newspeak describes denunciations.

It is clear that this is the tip of the iceberg, because there are also appeals from citizens to the police, the Investigative Committee, the FSB and other law enforcement agencies.

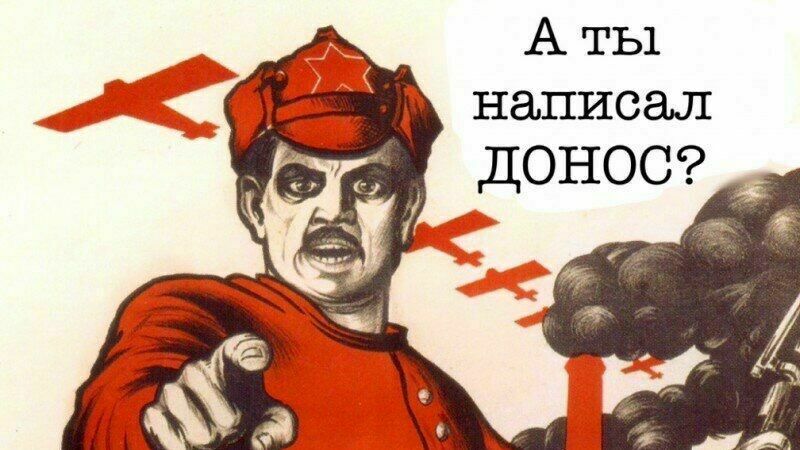

Whistleblowing becomes "salon", at least on the Internet. In addition to special sections on the website of each department, where Russians can tell about offenses, helpful defenders of the Russian state have made a separate page "Denunciation.the Russian Federation", where all resources are collected for the convenience of complainants – so that, as they say, they do not get up twice and send applications to all instances at once. "Fair Russia" got busy in the spring and opened its website for informers. The page is currently unavailable. Apparently, the complainants are also not blindly sewn, they did not want to promote the Mironov-Prilepin-Prigozhin party and immediately turn to "where it is necessary".

In any case, there is a mass phenomenon that is growing and expanding day by day.

WHO ARE THE RUSSIANS ARE INFORMING ON

According to the Ural media, from March 4, when the law on "fakes" was adopted, to October 18, 2022, about 650 administrative cases were initiated in the region, most often against those who disagree with their own and express their anti-war position in social networks.

Teachers often fall under slander, as it was, for example, in the city of Nizhny Sergi, Sverdlovsk region. The teacher was denounced by the grandmother of two grandchildren – a seventh-grader and a ninth-grader. The vigilant old lady wrote "where it is necessary" when she heard from them that the teacher "gave a negative assessment of the activities of the president and the Armed Forces." The teacher was awarded a fine of 15 thousand rubles.

People are fined for "incorrect" posts and statements in private chats. Orenburg resident Konstantin Pchelintsev ran a marathon with the flag of a neighboring state on his T-shirt and paid 30 thousand. In Saratov, the doctor Selimat Asmanova was fined the same 30 thousand on the slander of a fellow resident. On deputy Kruglov from the Yabloko party, a certain Anna Vasilyevna K. wrote a denunciation. The deputy, giving an interview to "Rain"* (the TV company is recognized as a foreign agent in the Russian Federation - ed.), according to the applicant, violated the law by not correcting the presenter. "You see, I did not correct Ekaterina Kotrikadze*, who called "SMO" another word — and thereby, by not correcting the presenter, discredited the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation," Kruglov wrote in TG.

The degree is increasing both among citizens and on the side of the authorities. It comes to the point of absurdity. In Krasnogorsk, near Moscow, a man denounced himself. After drinking a lot, he wrote "bad" inscriptions on the wall of the house. When he sobered up, he ran to the police himself out of horror and repented. The administrative protocol was brought against him after all.

Ivan Losev from Chita made a mistake by retelling his dream about Zelensky. Who wrote the denunciation, he does not know. Chitinets paid 30 thousand for a dream about the Ukrainian president. But the matter did not end there: Ivan then talked to journalists, for which he received another fine. The court unequivocally sent greetings to Losev: don't talk!

TYPOLOGY OF DENUNCIATIONS

Historian, First Vice-president of the Center for Political Technologies Alexey Makarkin identifies four types of denunciations that have existed since the Soviet era.

Since this form of information transfer served as a specific means of stimulating the movement of an official up the hierarchical ladder (i.e., a kind of factor of social mobility), so far as "professional denunciation" can stand in the first place. Then comes his household form, when in this way they want to get rid of a competitor (neighbor, colleague, etc.), having no desire to take his place in the official table of ranks. Of interest is such a common type of informing the "competent authorities" in the USSR and other totalitarian countries as "related denunciation", when the informer and his victim are related to each other (mother, wife, brother, father, son).

However, these forms are mainly individual (or narrow-group, including from two to five people) in nature, are implemented in private, assume a certain secrecy from other persons. Meanwhile, group denunciation was also widespread in the USSR, when hidden information about individuals was made public publicly, at various meetings, which implied an immediate reaction to it by the authorities.

A similar form of denunciation (in the military collective of the mid-1930s) is shown in G. Y. Baklanov's novel "July 41" (apparently, the author observed it personally). The hero of the book, General Shcherbatov (at the time of the events described, the battalion commander, major) recalls speaking at such a "meeting-exposure" of his subordinate captain, the company commander. The latter, coming to the podium, said:"– Comrades!

The political moment that our country is going through, the titanic struggle that the party is waging under the leadership of... leader and teacher Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin… this struggle requires from... us not only vigilance, but also party principles... Let's ask ourselves, as a communist of a communist…: “Are we always able to rise above personal, friendly relations?”... Not always! Here is a colonel sitting among us… Masenko… But you are insincere in front of the party… In the twenty-seventh year, do you remember, you attended a meeting of Trotskyists?In practice, the separation of these types of denunciations is extremely difficult.

For example, a "household" denunciation could quickly turn into a "professional", become "related", "public". "Professional" – to pursue purely "domestic" goals.

Denunciations have always existed, experts say, but their number differed sharply from period to period.

During perestroika, the number of informers sharply decreased, and all 4 types of denunciations were sharply condemned by society. When perestroika was over, disappointment set in. Denunciations as such were not rehabilitated, but black became white, and white became black. First, the rehabilitation of Stalin began, and then Beria.

"Already Lavrenty Palych Beria became a hero first as the organizer of the atomic project, and then as a vigilant and fair people's commissar of the NKVD, who did not chop off heads right and left, as mentally unstable Yezhov, and quite rationally engaged in repression against quite real enemies", describes the mood in the country historian Makarkin.

Against the background of the whitewashing of the "heroes" of Soviet totalitarianism – Stalin, Beria, Lysenko – denunciation again became part of patriotism:

- They argued like this: look, they didn't inform, if someone had reported that Gorbachev was so delighted with France when he went there, being the first secretary of the regional committee. If there had been a denunciation against him, there would have been no perestroika. Maybe then we would have won the Cold War? Or has someone ratted on Yeltsin that he actually sympathizes with the dispossessed? You never know? Or has someone ratted on Gaidar that he, as an economist, evades Marxism-Leninism? So they didn't inform, and then these people came to power and caused trouble. Therefore, informers are useful to us.While the political processes in the country were moving towards liberalization and openness with the work of government agencies, informers were ignored.

With the advent of quasi-ideology, "spiritual bonds" and a new wave in the fight against dissent, the state appreciated the benefits of whistleblowing, and it flourished again.

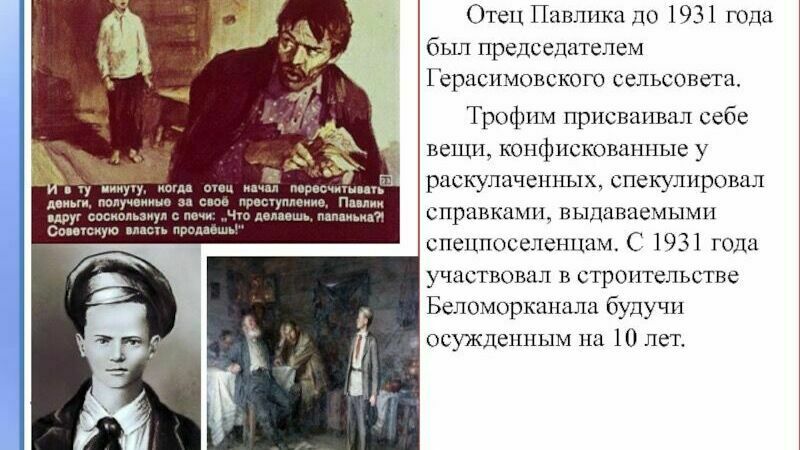

Against this background, the history of society's perception of Pavlik Morozov as a symbol of denunciation is interesting. In Soviet times, the boy was included in the pantheon of heroes, whose names were called pioneer detachments. During perestroika, Pavlik Morozov lost his halo and became just an unhappy child who sent his own father to the White Sea Canal. Now there has been a revision of values again, and Pavlik is again a "hero".

WHISTLEBLOWING AS A DISEASEIt is naive to believe that snitching was born in the USSR.

No, it exists in all countries and at all times. And it was not only in the USSR.

Historian V.A. Nekhamkin writes in the journal "Historical Psychology and Sociology of History":

"His disciple Judas, who denounced Christ, ended his days violently: according to one version, he was killed, according to another, he committed suicide. An episode similar to the biblical one took place with a real character. In 43 BC, a disciple of Marcus Tullius Cicero, nicknamed Philologist, "brought up by Cicero in the studies of literature and sciences" (Comparative Biographies. Cicero 48), informed the assassins sent by the triumvirs (Octavian Augustus, Mark Antony, Lepidus) of the location of the teacher. In "gratitude" for the denunciation, the authorities handed over the Philologist to the wife of Cicero's brother, Pomponia, who ordered him to be brutally executed (Comparative Biographies. Cicero: 49.213). Meanwhile, the number of informers steadily increased, which caused serious concern to the authorities. In 79-81, the Roman Emperor Titus began the fight against informers at the state level. By that time, thanks to periodic civil wars and the actions of the previous rulers of Rome (Caligula, Nero, etc.), according to Suetonius, "the long-standing arbitrariness of informers and their instigators" had become "one of the disasters of the time" (The Life of the Twelve Caesars 8.8(5)). This social "disease" was also treated cruelly. Titus "often punished informers at the forum (i.e. publicly. – V. N.) with whips... and finally ordered them to be led around the amphitheater arena and partly sold into slavery, partly exiled to the wildest islands." Tit has also taken a number of administrative and legislative steps to eradicate whistleblowing. However, it was not possible to destroy the phenomenon itself and the problems caused by it in this way in Ancient Rome."In this fragment, it is important to note the role of Emperor Titus and his state, which fought against informers, whereas in modern Russia we see the opposite picture.

Historian Evgeny Ponasenkov (recognized as a foreign agent in the Russian Federation - ed.) He sees a clear medical diagnosis in the persistent desire of some fellow citizens to hurt and punish dissidents. A remarkable scientist, neurophysiologist Bekhterev very accurately described collective, social mental illnesses. He proved that mental illnesses exist not only in the individual, but also in society. Whistleblowing is one of these diseases, certainly one of the most harmful, says Evgeny Ponasenkov:

- By this, they do not love any homeland, they hate Russia and hate the Constitution of Russia, they hate Tchaikovsky, they hate the great artists and writers of Russia. Russia is Tchaikovsky, Pugacheva, Pasternak, Brodsky, in the end I, I create the Russian language in all genres. Both scientific and artistic. And they are anti–Russia, they do not create either science or art.Social psychologist Alexey Roshchin believes that with the transformation of the country into an analogue of the USSR, all the attributes of the past return.

In Soviet ideology, denunciation was one of the most visible manifestations of loyalty. There is another reason – the mentality of the people:

- We do not like open conflicts, they try to avoid them by all means, not to run into, not to stick out. Denunciation allows conflict to be avoided. On the one hand, people are afraid to speak openly, on the other hand, irritation accumulates. Whistleblowing makes it possible to conflict without conflict. You write to the authority, the person is taken away, and at the same time you can maintain excellent relations with him, say hello and be interested in the health of your mother-in-law. There are no unpleasant experiences due to an open conflict.Denunciation for a quiet and non–confrontational person is the ideal way out.

It allows you to vent aggression and leaves you safe and relieves you of responsibility. All the trouble will be caused by other people:

- There is a universal excuse that protects against remorse: I just signaled, and if something went wrong - a person was imprisoned, beaten, tortured – it wasn't me who did it, it's the state, – the psychologist describes ways to evade responsibility.

Again it seems that it's forever – until it endsSociologist Lev Gudkov, scientific director of the Levada Center (recognized as a foreign agent in the Russian Federation - ed.), argues that it is not worth exaggerating the problem of denunciations.

In any case, sociological measurements show that ordinary people distance themselves from political snitching, there are not so many radicals:

- A lot or a little depends on which group we take. In relation to the entire population, they are marginals. Angry, aggrieved people, or careerists. Included in the political system, activists of the EP, LDPR, motivated are knocking... But there are very few party members. We once talked about this topic with Arseny Raginsky, who strongly refuted the thesis that half of the citizens of the USSR were knocking on the other half. There were not so many denunciations. The KGB did not like the so-called "initiators", relying on their agents. Now the authorities look favorably on their flock, the sociologist states:

- There is an ideological provision for informing. From state institutions, of course, there is encouragement of the worst in people, stimulation of informing. "Knock, and you will be rewarded." It goes almost in plain text. They do not call the verb "knock", but urge "to be vigilant".The experts we interviewed believe that the situation with whistleblowing will worsen.

As long as the cold war with the West continues, the whistleblowing will continue. We are facing a sharp increase in tension, bitterness and conflict. In these conditions, the number of informers will grow, Lev Gudkov believes.Historian Alexey Makarkin is sure that when the socio-political situation calms down, the activity of informers decreases:

- Of course, they remain and do not go anywhere, but their number and activity are decreasing. During the thaw, the number of informers decreased, not because human morals improved, but because the state stimulated less. Plus there was fear. Some people who actively denounced under Stalin had a fear that either the state would sort them out, or the victims would sort them out. Gradually, the fear went away, because the state decided to close these topics.An interesting fact: measurements of how society treats informers were not carried out.

However, in a country where political repression has affected 11 million people, and this is not counting their families, and 10 million peasants, there is, on the one hand, hatred of informers, and on the other hand, fear. That hasn't changed.

by the wayAn interesting conclusion was made by publicist Sergey Medvedev, speaking about the attitude of the "deep" Russian people to informers:

"A snitch in Russia is a shameful stigma. From time immemorial, the collective has been united against informers, building rituals of mutual responsibility, silence and non-reporting: a sneak is beaten at school, an informant is ostracized at work, a snitch can be strangled in the zone. A vow of silence, like a mafia omerta, is a sign of distrust of the authorities, our defense against a repressive state. In Russia, in this sense, there is no "society" as a sociological category of Gesellschaft, that is, a contractual, impersonal collective in which people are polite, alienated and control each other. Our unit is a community, a Gemeinschaft, where people are connected by relations of blood, kinship, common faith, common cause, like the same mafia fraternity. Hence the mutual responsibility, and the conspiracy of silence, and contempt for informers."